Making the Convention on Modern Liberty

Making the Convention on Modern Liberty

The back of the Guardian Wednesday 11 February 2009

This is an overview of the creation, development and achievements of the Convention on Modern Liberty, held on 28 February 2009. It is backed up by a set of documents. It will be published on the archived website of the CML. It is by the executive team, drafted in the main by Anthony Barnett. As far as possible it does not include their opinions nor is it an account or analysis of the day, with its many speakers. Video of the plenary sessions of the Convention and its 22 parallel workshops and debates, transcripts, briefing papers, the programme, the minutes of the planning meetings and the full lists of all who worked for and helped fund the event, and links to coverage, can be found on the archive website www.modernliberty.net. The aim of this short account is to set out the aims and intentions of the London Convention and how these were accomplished – or not. The planning, development and execution of the seven Convention gatherings outside London are not covered here, despite their importance.

How it started

Three forces combined to create the Convention on Modern Liberty. They were brought together by the resignation of David Davis MP from the House of Commons (and his position as the Conservative opposition shadow Home Secretary) on 13 June 2008. The three were: The Rowntree Trusts, openDemocracy, and Henry Porter in his role as an Observer/Guardian columnist.

The resignation On 12 June the Commons backed Gordon Brown’s decision to extend detention without charge for possible terrorist offences to 42 days. The next day, David Davis walked out of the Commons in protest, to force a by-election in his constituency of Haltemprice and Howden. Davis made a statement saying that the 42 days policy was an attack on Habeas Corpus rather than an anti-terror measure, that the establishment of a database state should be reversed, and that the growth of a surveillance society had to be stopped. For such opposition to have the chance of durable success he said it was essential to show that the public cared about the issues, because parliament had failed the country. Therefore he felt it was his duty to appeal directly to voters.

These five issues: 1) the failure of parliament, 2) the need to arouse public opinion, 3) the requirement to stop the abuse of anti-terror measures, 4) the importance of alerting the public to the rise of the database state, 5) the nature of unregulated and unaccountable surveillance, together form the core concerns of modern liberty in Britain.

Rowntree Trusts: On 20 June, a week after Davis’s stand, Mark Ross of the Joseph Rowntree Reform Trust (JRRT) wrote to the organisers of the small seminar series it and the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust (JRCT) were funding. The organisers were Stuart Weir from the Democratic Audit, Anthony Barnett from openDemocracy’s OurKingdom and Peter Facey from Unlock Democracy. Ross had already spoken to them informally about the need to give the issues which Davis had raised greater public salience.

One idea that I’m really interested in is for someone to organise a major public meeting in London, with 300+ people, pulling together the whole liberty agenda. Davis could be asked to give the keynote to a packed room, with cross-party support on the platform (Helena or Bob Marshall-Andrews, maybe Clegg, etc, as well as Shami). It should get good media coverage; it might even be possible to organise a media sponsor (Guardian, Indy or Telegraph). Any thoughts?

He added that a small grant would be likely to support scoping out a proposal.

openDemocracy: The second source was the strong and convivial encouragement of Tony Curzon Price, Editor-in-Chief of openDemocracy who backed his predecessor Barnett’s suggestion of hosting a project saying he wanted open debate, high purpose and the exploration of new ways of taking the core issues of democracy and liberty to the public.

Henry Porter: For three years, Porter had been covering the issues in his outstanding Observer column, sometimes published in the face of official pressure. As far back as 17 March 2005 at the memorial service to Anthony Sampson, Porter had suggested to Barnett that a public event was needed to draw attention to the issues. At his initiative they had met to discuss how this could be done and emailed with increasingly frequency.

With Porter’s support, Barnett and Weir submitted a proposal to the JRRT on 26 June 2008 for an “enabling grant” to scope a “teach-in”. (Doc 1). It set out five aims:

1. Widen the alliance of those concerned to prevent 42 days from becoming law

2. Greatly extend public understanding of the larger issues raised by the database state

3. Create an event that will help build a campaign to persuade the Lords to repudiate 42 days

4. Challenge the view that the public support populist measures

5. Help recruit the younger generation to a democratic approach to politics

A grant of £5,000 was promptly made by the JRRT and Barnett was joined by Claire Preston. They set about finding a suitable venue available in time, drawing up a budget and putting a full proposal. Preston was to provide vital and steady administrative support for eight months. On 4 August Alan Rusbridger, Editor in Chief of the Guardian group emailed Porter to say they would sponsor such an event.

A longer draft proposal was drawn up by 18 August. It had three parts: a description of how the event would work with a proposed date of 25 October. It included extensive web and video coverage; an outline of possible of plenary and parallel sessions; and a draft public statement of aims. (Doc 2)

This document was used to explore potential funding (for a then estimated total budget of £40,00 grants plus significant ticket revenue). Sir Geoffrey Bindman, chair of the Open Trust and his fellow trustees agreed to support the Convention. John Jackson pledged £5,000 over the phone conditional on full funding and Elaine and David Potter emailed on 23 August to say, “We’ll be happy to support you with £10,000 assuming you can put the whole thing together. The whole event sounds important and worthwhile”. The promise of independent funding and Guardian sponsorship encouraged the JRRT which confirmed it would put up a further £5,000, but on condition that the JRCT came through with £10,000.

Stephen Pittam of the JRCT argued that it was essential to ensure that the proposal did not split the human rights community from those concerned with liberty. Barnett supported this approach and worked to ensure the cooperation of Liberty, which both saw as decisive to achieving this.

With a third of the then projected costs secured and a further third from the two Rowntree Trusts likely, there was an initial meeting at the Guardian with Georgina Henry, its Executive Comment Editor, and Mark Sands in charge of marketing and sponsorship, which Pittam joined. By then the proposed date had shifted to 29 November and the venue to the Institute of Education’s Logan Hall, with seating for 900 and good rooms for smaller, parallel breakout sessions. The meeting set out a framework for Guardian sponsorship (Doc 3).

At the same time core recruitment was taking place. Barnett asked Guy Aitchison of openDemocracy’s British blog OurKingdom to look at the proposal on 13 August. He expressed his excitement and began to help informally. He became the Convention’s full-time Deputy Director. Phil Booth of NO2ID was approached by Barnett as heading the most active organisation on the ground across the country motivated by concern over what the state was doing. He agreed they would run the day in London and host out of London meetings to be web-linked to the main event. Bill Thompson was approached the build the website for which a spec was drawn up by Curzon Price. Sunny Hundal editor of Liberal Conspiracy gave his support and agreed to host a bloggers summit with the Guardian’s Comment is Free. All this fed into a proposal which was drawn up for a sponsors meeting on 18 September 2008 to included Shami Chakrabarti of Liberty. This was held in at the Guardian offices, (Doc 4). There was a tension that was to continue between a one-off event and a movement. But the draft ‘call’ was amicably discussed and amended. Liberty agreed to became a co-sponsor.

The meeting’s successful outcome of marked the end of the development period and the starting date of the CM proper (Doc 5). There are four points to note here: 1) the decision to call it a ‘convention’, 2) the branding, 3) the budget, 4) uncertainty

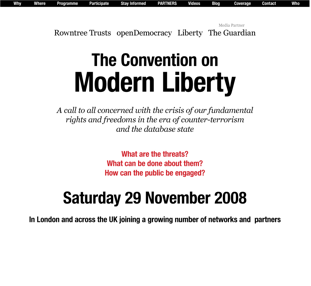

Convention: Porter insisted that we did not want a ‘teach-in’ as the term was too vague. Our aim should not be to hear every possible view but rather to explore in an open way the ideas and arguments of all those who supported if not a ‘call to arms’ then a ‘wake up call’ to the public on the crisis of liberty. This led to our calling the event a Convention, meaning a gathering with a sense of purpose. This decision, taken before the 19 September meeting and accepted by it, set the tone, character and body-language of what followed. The draft described the event as:

A Convention on Modern Liberty

Calling together all concerned with the crisis of our fundamental freedoms and human rights in the era of counter-terrorism and the database state

- What are the threats?

- What can be done about them?

- How can the public be engaged?

While the 18 September meeting improved and expanded this wording – the approach had been established.

Branding and Partners: The meeting of the 18th agreed that the there should be four lead sponsors: Rowntrees, openDemocracy, Liberty and the Guardian. The Democratic Audit stood back, though Weir its Director, played an important role introducing the draft programme. NO2ID was not included as top-level sponsors at the start. Nonetheless a key ‘brand’ for the whole event was a strong emphasis on joint cooperation with as many partner organisations as possible. Possibilities were listed in the draft proposal and some had already been sounded out. To bring together organisations and causes with different histories and interests and their own strategies naturally creates tensions. These can be to the good and need not be destructive. Taking them on board is an essential part of any attempt to widen the influence of civil society.

Budget: By the time of the 18 September meeting £28,000 of funding had been committed, considerably more than the £15,000 the JRCT and JRRT were considering. However, the projected budget of £40,000 of grant income on top of ticket revenue was a serious underestimate. Webcasting and filming were both expected to be done for free, no allowance was made for out of London meeting costs, there was only one full-time person on the organising team allowed for in the initial budget, the Deputy Director. Finding additional funding became a constant preoccupation (on the other hand, if the full costs had been set out at the start it might never have happened).

Uncertainty: The unwarned reader of this brief account might think that, as it describes how each step was taken in turn, everyone knew what they were doing. In fact the entire development of the CML up to the day itself was accompanied by a powerful sense of uncertainty and a strong experience of high risk. Throughout 2008 it was unclear if people would ever heed a wake up call at all. Would other media cover the event if the Guardian did? What impact might the financial crash have (see below)? Would there be enough money? None of the executive team had ever webcast. The use of video to support an event was an innovation. Most of the team had never organised a major conference. Perhaps most important of all, there was no such thing as a Modern Liberty organisation in place to call on its members to support it, while its host organisation openDemocracy was a web publication without any on-the-ground network of organisers and supporters. We gathered in considerable resources and media backing but the whole thing was from beginning to end an ad hoc learning experience rather than a plan.

After the 18 September intensive development got under way. Partner sessions, driven forward by Aitchison, were put together. Some went well: John Jackson got Mishcon de Reya to sponsor one on the law and parliament and distinguished panellists were approached; Peter Facey at Unlock Democracy; Becky Hogge at ORG (the Open Rights Group); Lisa Appignanesi at PEN, came through quickly. Amnesty International were very positive but later fell away. Philip Pullman agreed immediately to be a keynote speaker. Other well known figures declined.

By the end of the month Clare Coatman agreed to join as an intern in charge of ticketing and was to become a lynchpin of the organisation alongside Aitchison, she soon became the CML’s full-time Participation Manager.

The target date to launch the website by 1 October slipped as its spec altered. Bill Thompson built it in good humour to a design by Dai Kurebayashi Williams based on an eccentric desire by Barnett to mimic 18th century pamphlets.

Nonetheless, as October began the first enquiry came in. Thanks to William Sieghart, a TASK grant of £15,000 from Esmée Fairbairn Foundation meant we were funded to the full amount we then thought we needed. Speakers were being booked, the first advert in the Guardian was initially scheduled for 14 October. The first online reference to the Convention was run in the Guardian’s Comment is Free, by Barnett on 6 October.

But it became clear that while, with a big push, the Logan Hall could be filled with 900 people on 29 November, the sheer effort of doing so would take all the team’s time and there would be no resources to invest in the wider, public impact which was the main point of the wake-up call. On October 8 it was decided to see if we could get agreement to move the date to 28 February when, fortunately the Logan Hall was free – the only Saturday it was available in the new year. Speakers like Philip Pullman preferred the new time and funders agreed it was preferable. The decision was taken on the 9th. As we wrote to speakers who were already booked: “We can fill the theatre on the 29 Nov. The responses are strong and encouraging. But we may not light the touchpaper of a wider movement of opinion”.

Another reason for postponement was the financial crisis, which was engulfing everyone’s attention. Lehman Brothers had gone into liquidation on 15 September. Already at the Guardian meeting on the 18th when the CML officially began, its likely ongoing impact was identified as something that might over-shadow the issues of liberty and rights in the UK. (Indeed, according to an authoritative US insider quoted by Robert Skideski in his new book, $550 billion was being drawn down from US money-market accounts in an “electronic run” in New York that morning. at the very time we were meeting, and if they had not promptly been closed “the entire economy of the US and within 24 hours the world economy would have collapsed”). A slower decomposition of British banking followed. RBS and HBOS were to be rescued on Monday 13 October, when they were just hours away from closure. In the month between the ongoing crisis dominated politics. It was right to extract the Convention from the maelstrom.

Initially we were very worried that fear of financial ruin and a thirties style depression would make liberty seem a ‘luxury issue’. If anything, the opposite happened. While people were arguably cavalier about their loss of formal liberties as the promise of financial freedom ballooned, the idea of losing their basic rights and freedoms as well as their jobs and prosperity suddenly made liberty all the more precious. If anything the financial crash reinforced the sense of the system turning against citizens and the need for a new politics. The presentation of the Convention was changed and we added the financial crisis as a threat and new panels to debate it.

The February timing allowed Porter to propose a launch event for influential ‘big-hitters’ and to plan bringing in a PR agency. Both would significantly intensify the wider impact of the Convention.

Decisions were taken in an efficient and open fashion. The Convention was run by Barnett and Porter as Co-Directors, each respected the other’s right to act in the Convention’s name. Many of the panel invitations were made by Aitchison and administrative decisions by Preston and Coatman on the principle that they should decide as they thought best and only consult if they felt it was necessary.

In addition to what can be called the ’sponsors meetings’ (18 September, 2 December, 21 January, 5 March) from the middle of October planning meetings were held most – but not all – weeks on a Wednesday afternoon to coordinate the growth of the Convention, identify problems and share proposals. The principles of the meetings were: 1) only people who were actually doing something attended and no one ‘represented’ an organisation, 2) anyone who attended could make any suggestions they wished on whatever topic was being addressed, 3) the meetings would be 90 minutes and were often less, giving people time to chat and talk informally, 4) the website was projected to ensure that the Convention was looked at with a vivid sense of the public in mind, 5) decisions and issues were recorded and minutes rapidly circulated.

Sponsors meeting, 21 January 2009 at the oD/Accountability office, Goswell Road, from left to right:

Henry Porter, Sabina Frediani, Stuart Weir, Guy Aitchison, Helena Kennedy (video image on screen), Rosemary Bechler, Phil Booth, Mark Ross, Denise Scott Fear, Anthony Barnett (back to camera).

None of this would have worked without full use of the web as an organising tool, with shared spread sheets for speakers, eventbrite for tickets, skype and powwow conference calls, and, an innovation introduced by Stephen Taylor of NO2ID after he joined, the use of basecamp as the CML’s organisational tool.

Taylor was invited by Booth to volunteer on 21 October, to help with running the stewards on the day. He generously did so and became a central member of the team. Christina Zaba from NO2ID in Bristol and its trade union officer also became an important part of the organisation. She worked with Rosemary Bechler, whom Barnett had approached as someone with the experience to look after the Convention’s partnership network.

Everyone involved worked very hard; especially on getting speakers, such as Dominic Grieve. Ken Macdonald, Marina Warner, Brian Eno and Lord Bingham while Taylor used the NO2ID and other networks to recruit a stewards group. Lively debates on proposed panels (police, Muslims), making sure organisers sent in their descriptions, honing the overview statement, inviting new partners, continued daily. This effort was supported by individual generosity, for example when Neil Tenant came through with a donation.

There were regular frustrations and refusals as well, naturally. Just one can be mentioned – to stand in for all of them. The British Library was holding an exhibition called ‘Taking Liberties’ that displayed together for the first time many of the key documents of the fight for liberty and rights in Britain from the Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest and the Declaration of Arbroath to the Agreement of the People, the 1832 Great Reform Act to Charter 88. We proposed a special panel linked to the exhibition. The BL had sponsored Liberty to hold meetings at the party conferences in 2008. But it turned us down, as its official explained on 31 October:

Even though I understand such sponsorship is not financial but promotional, the Library is unable to lend its name to this event and the Convention, I’m sorry, for the following important reason. The British Library is and must remain politically neutral. In the context of a major exhibition we can set out collection items into a historical narrative and link those with the issues of the day but we are not driving an agenda. The Convention on Modern Liberty is.

Oh well. The exhibition, with its clenched fist symbol, was hardly neutral in its celebration of its core theme. Indeed, it was opened by Gordon Brown. He had originally encouraged it as part of his ‘Britishness’ positioning (or ‘agenda’ if you will). But by the time it opened he was bruised by the frustration of his 42 Days policy. Privately, we heard a rumour that the Cabinet Secretary called the head of the BL and warned against the exhibition becoming “political”.

By early November the budget reflected the doubling of the Convention time frame and the full demands of running it, including three full-timers working for seven months. The total was projected as being £97,000 including 10 per cent contingency but still nothing for professional PR or filming and webcasting. £71,000 had been raised in grants and £26,000 was projected in ticket sales. Tickets were projected at £30 (this was raised to £35) to include full catering through the day with student tickets at £20. A third of all tickets were assigned to them to ensure a high proportion of the younger generation.

The Logo An appeal had been sent out by Tamara Barnett-Herrin to designers she knew saying ‘Modern Liberty needs a Modern Look’. Leon Harris was the most convincing of those who answered and after discussions on 19 November he proposed some designs that included what immediately became the CML look and logo (Doc 6).

Harris became the Convention designer. He did the Guardian and Observer adverts and the programme as well as a range of announcements and widgets. His flexible design and logo, with its classically modern look and dynamic web capacity to change its colours, adding considerably to the lustre and originality to the Convention’s impact. Here is one early quick and dirty example.

The Co-Directors had paid a visit to Gemma Gordon-Rogers at Agency Republic to ask for advice on viral marketing. A young designer Dan Collier was ‘fired up’ and concerned that the role of video was not strong enough. On 27 November, off his own bat he sent a ’skin’ for what he thought the website should look like.

The result was the tough decision to build a new website after Curzon Price observed that this one was “much better”. All the crucial back-end work on the new website with its inspired integration of video was implemented with tremendous speed by Tom Ash, who had became part of the CML team in mid-October after he joined openDemocracy, helped by Rob Sharp and Harris.

In the six weeks from the new site launch on 18 January 28 February, over 2,000 links were made from across the web, there were over 30,000 absolutely unique visitors, over 50,000 visits and over 200,000 page views (Doc 15)

On 2 December a small sponsor’s meeting was held at the Liberty offices attended by Pittam of the JRCT. This agreed that the aim was both to inspire a movement that would continue if it “caught the zeitgeist” and that no organisation called Modern Liberty would continue after the event. Again the tension of motives was evident.

Ticket sales, using the original website as the platform, started on 10 December, the 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights – and the warning, evidence of our nervousness, that had been on the website since it went live “Event Under Construction” was finally lifted. The first press release was issued (Doc 6). The Countryside Alliance and the TUC agreed to participate, expanding our reach and together representing the cross-spectrum nature of the CML’s appeal. A leaflet was designed to attract young people (Doc 8) and fill the third of all London tickets assigned to them.

As the event itself started to shape up Porter circulated (on 1 December) a brief for a professional public relations campaign (Doc 9) and set out the plan for launch party – that was to be held on 15 January at the Foreign Press Association in Carleton House Terrace. He personally financed it. Helena Kennedy agreed to co-host it with him and Vanity Fair sponsored it. The first 300 invitations went out on 9 December.

The last Wednesday planning meeting of the year was on 18 December. Seventeen people crowded into it. Inspired by the design of the new website Portia Barnett-Herrin volunteered to make short videos. The first with Helena Kennedy and Peter Oborne were filmed on 22 December. Porter reported that Robin Lough, whom he had approached, had volunteered to film and live edit a three-camera team on the day (but it would still cost to get the crews and equipment).

The New Year

Over the next two months activity intensified both in terms of the internal creation of the Convention and in seeking to maximising its public impact.

Internal: finalising speakers and sessions; briefing speakers and session organisers; the organisation of the day; webcasting; recording the sessions; producing the programme; fundraising; the non-London meetings.

External: the launch party; Guardian coverage; social networking and the blogosphere; the videos; the briefing papers; adverts; partner publicity; PR and media coverage

These activities reinforced each other:

- The launch party provided a focus for media and getting the word out in circles of influence; it also helped fundraising and inspired some speakers.

- The programme was conceived as a guide to the day with its many sessions but it was also a means of offering partner organisations free advertising. This deepened the conversation with them as to why they should support the CML and tell their members about it. It was an often diplomatically testing operation. It was led with exemplary judgement by Bechler who was assisted by Alice Dyke.

- The non-London meetings had a very important external impact as they embodied the Convention’s determination to take the issues across the whole of the UK and ensure they were not seen as just metropolitan. But each of the seven parallel events in Belfast, Birmingham, Bristol, Cambridge, Cardiff, Glasgow and Manchester had its own internal organisation and achievements. Belfast was organised by Patrick Corrigan of Amnesty International; Birmingham by Gargi Bhattacharyya; Cardiff by Caroline Oag of UNA Wales: Vale of Glamorgan; Bristol, Cambridge, Glasgow and Manchester were put on and run by their local NO2ID organisers, with city media coverage and a neatly adapted logo in Glasgow. All seven were coordinated by a hard-working Booth.

The Guardian started its coverage on New Year’s Day with a CiF post by Matt Seaton

Also coming over the horizon, the next exciting new development will be the launch in a few weeks’ time of a new Cif civil liberties site – to coincide with The Convention on Modern Liberty taking place on Saturday February 28 2009, which is sponsored by the Guardian (for further details, see here, and for ticket and other information, see here).

On 7 January Sir David Varney the leading author of the ‘Transformation of Government’ programme that had set out the framework for the creation of the database state agreed to attend.

Our marketing strategy was almost exclusively web-based using the economies of social networking. This is the best place to summarise how they developed.

We used mailing lists and social media to reach thousands of people directly, raising awareness of the Convention, driving traffic to the website and boosting ticket sales. Subscribers to the Convention mailing list grew to 1,466. We sent out updates roughly once every two weeks. There were 2,115 members of the Convention Facebook group which allowed us to post news and updates on the group wall and message members directly. The group forums were also used to host discussions. We had about a thousand followers on Twitter. Towards the end of February Guy Aitchison was sending around 8 updates a day linking to Convention material.

(On the 28 February itself Twitter was also used to good effect by people at the different meetings across the country and watching at home online. The Conventioneers conducted a live nationwide conversation using a CML hashtag. At one point it had the third highest profile of anything on Twitter. And there were hundreds of photos in the Convention flickr group with users posting their own.)

We started using Crowdvine, a user-led social network, a week before the Convention to encourage participants to make links with others interested in civil liberties campaigning and take action. Crowdvine allows you to commit to specific actions (there is a list of calls to action issued by our partner organisations) and find other people in your local area on interested in campaigning. There were around 200 users and an initial flurry of activity on Crowdvine. This would have needed ongoing leadership to be sustained – it showed potential was there.

Engaging bloggers was a key part of our online strategy from the start. The launch of the Guardian’s liberty central site, especially the Liberty Central series of blogs on Modern Liberty, played an important role in drawing attention to the Convention and feeding arguments into the blogosphere. The Guardian was our number one referring site.

We tracked all the on-and offline coverage the Convention received on our Coverage page and blogged the most important of it. As well as providing a useful record for us this generated goodwill and reciprocity in the blogosphere. We also offered friendly bloggers small embeddable widgets for their sites which displayed Convention videos and buttons and banners featuring the Convention logo and over 50 websites and blogs carried a button or widget.

James Graham of Unlock Democracy and the Quaequam blog launched ‘Carnival on Modern Liberty’ His initiative was neat and effective: its aim to promote debate on civil liberties in the blogosphere and spur both bloggers and their readers into action. The blog carnival provided a summary of the best to be found in the blogosphere on civil liberties, edited by a different blogger each week. It was hosted on a wide range of blogs, including Liberal Conspiracy, Lib Dem Voice, OurKingdom, Yourksher Gob and was reproduced on other blogs, including LabourHome.

In contrast to cyberspace, back on earth costs were rising. A new overview and funding document was drawn up by Barnett (Doc 10). It included Porter’s extensive research into PR companies, four was initially selected. When this didn’t work out we happily joined forces with Dotti Irving’s team at Colman Getty. The document also appended Porter’s case for briefing papers (Doc 11). The whole proposal was sent to existing and potential new funders seeking to raise at least a further £30,000. This is how it set out the plan on 11 January:

Current state of play

The Convention on Modern Liberty will be held on Saturday 28 February 2009. It will be launched on 15 January at a party organised by Henry Porter… print media coverage will start with a ‘call to arms’ in the Observer on 18 January and the first advert in the Guardian on 19 January. A new website, whose design was conceived for free by staff at Agency Republic, should go live on 17 January, carrying the first of a series of new short videos made for the Convention by its supporters and speakers.

The document also set out the Co-Directors’ vision:

“What’s the aim?

We have been asked what will be different on March 1st? We hope it will witness the birth of a movement. The Convention is an event. It aims to bring together and debate the many connected issues, outrages and abuses that threaten our fundamental rights and freedoms in contemporary Britain. Should it succeed people will feel less isolated and fearful, organisations will feel strengthened, public awareness will be heightened and become more intelligent and articulate, media coverage will greatly improve, and the United Kingdom will – eventually – become a home for modern liberty.

Of course, a birth can mean bringing into the world a bawling, sprawling, uncoordinated, hungry and protoplasmic life force that may not survive. Its strength and personality will take time to develop. We look forward to it with anticipation – but not with detailed plans. These would be inappropriate. Certainly we want to see changes in government policy and an end to the building of a database state. But we are not seeking to create a new organisation with a programme of demands for reform in Whitehall. These exist already. If we can, our aim is to help them by widening the context of their appeal. We are not looking towards Westminster but outwards. Our aspiration is to influence the country’s political life and its public spirit in the belief that only the people themselves will be able to ensure the change of course Britain needs in order to secure our freedom and fundamental rights.

This is a big expansion of our original ambition – it has been lifted by the exceptional support, enthusiasm and creative input we have received….

The launch party on 15 January was a success. Porter took care to spruce up and brand the magnificent house in Carleton House Terrace, once the home of Gladstone. The event was packed, perhaps 400 came with hundreds more invited by Annabel Davidson. The invitation spread the word (Doc 12). The unusual mix of guests created a sense of excitement and gave the launch genuine energy, with Bob Geldorf and Michael Portillo making carefully casual appearances. If the speeches were slightly on the long side (Doc 13) the sound system worked. Keith Sutherland of Imprint Academic donated a full colour 16 page ‘taster’ of the programme for guests to take away, which showed off the glorious energy of the logo and the new website colours.

On Saturday, 17 January the new website went live with the first videos embedded. On the 18th Porter published an article in the Observer headlined: “Let the war on Hypocrisy begin”, writing:

If there is one overarching theme of the Convention of Modern Liberty it is that we demand that the public be trusted and respected by those in power. That means we will not tolerate the National Identity Register, or be forced to give 53 pieces of information to the government when we travel abroad, or submit to random searches at every possible opportunity, or have our communications data seized by the government and the sinister corporations with which it deals…. The Convention on Modern Liberty is for openness, reform, accountability, scrutiny, trust and fun. It is against the fixing, manipulation, suspicion, spin and self-serving edicts of the political classes.

The next day Georgina Henry launched ‘Liberty Central’ on the Guardian’s website with her article “Ringing the Liberty Bell“. And the first of three quarter page adverts appeared in the Guardian. The others were in the Observer on 25 January and 2 February – all the adverts including a paid full pager were coordinated by Preston.

On 21 January there was a sponsors meeting with Ross of the JRRT and Liberty, represented by Sabina Frediani, which Booth also attended as NO2ID became, rightly, a full sponsor. The minutes record a tension over the Convention’s possible afterlife and the larger aim of the CML

- Everyone was in agreement that there was no intention of starting a new membership organisation and that the mandate was to strengthen existing orgs and start a movement.

The Videos and the Briefings

Both the videos and the briefing papers were conceived to show that the purpose of the Convention was to address the public and not simply be a gathering of the converted.

Before the Convention the standard view was that the issues of modern liberty were “abstract” and of little interest to regular people. It was essential that we did not allow this view to prevail; or for the issues to become ‘constitutionalised’ and thus supposedly ‘arid’, ‘remote’ and ’specialised’ according to Britain’s anaemic political culture. Before the Convention could be thus stereotyped by the trope-addicted mentality of the official media, we got in the first blows. Journalists who went to the site to see what it was about found Helena Kennedy and Peter Oborne in short YouTube vids speaking in a forthright language anyone could understand. The videos also used witty written language to engage the viewer’s mental faculties. Barnett Herrin explained on 8 January:

These videos generate a basic aesthetic…Practical advantages of the approach are: it is straight to camera, does not have voice-over questions or mimic interview, but does not demand speaker is continuous, so has urgency and directness but not the pressure on the speaker of having to do all in one take.

Within a week of going live on 17 January Kennedy’s had over 1,000 views. By the Convention itself the team had made 22 videos (which had 33,000 total views) from Justice Minister Michael Wills and philosopher Anthony Grayling to Riz Ahmed, and from to Adnan Saddiqui to Damien Green MP. A two minute medley was made in mid-February designed for viral and got nearly 5,500 views. Perhaps the most original was a medley made after the Convention and embedded on 6 March. It showed the tension in the faces of those waiting to be filmed with an exceptionally eloquent voice-over from Brian Eno. The videos also acted as part of the direct draw of the event. A ‘Voices from the Crowd‘ video made on the day by an independent team includes a young woman at the Convention saying:

I am not entirely sure about how exactly I found out about the event, it was a link on something on the internet and then I started reading through and watching some of the videos and thought this is a really important event.

The Briefing Papers The Convention published six factual briefing papers (all open as pdfs):

- Innocence is no protection against the governmentʼs laws

- Whose life is it anyway?

- Has Britain become obsessed with petty minded control?

- Labour’s liberal rebels

- The personal questions the government wants us to answer

- The Abolition of Freedom Act 2009 (pdf)

They were produced by Miranda Porter and Matthew Brian, and edited by Henry Porter. A team of young researchers from University College London Human Rights Programme, led by Jonathan Butterworth, Tony Daly and Qudsi Rasheed, joined to help with the final paper on What we Have Lost which put into the form of an ‘Abolition of Freedom Bill’ the fifty measures that have intruded on and diminished liberty in the UK over the last decade – and threaten its extinction.

The Briefing Papers were designed to give journalists and broadcasters stories. They provided substance for the Convention’s PR campaign. Because they were factual and researched they created an authoritative case for the Convention, demonstrating that its concerns were not a matter of ‘mere’ opinion.

The Guardian and the blogosphere and beyond

There was plenty of opinion as well. The Guardian ran both print and regular CiF pieces including a piece by Lord Bingham and just before the Convention by Jack Straw. In total there were nearly 400 online articles or blogs referring to the CML.

By 8 February 622 tickets had been sold (420 full, 202 students and 30 at group rate) and with speakers and volunteers 867 places were confirmed. We decided to webcast from the main hall into the rest of the building, sell more than 900 places and tell all existing ticket holders that latecomers might not make it into the main hall, with its 900 capacity. On Wednesday 11 February we bought at a special rate, the full back page of the Guardian, listing 45 partners (who now including the Football Federation and Private Eye). The ad (illustrated on the title page of this account) further increased demand for tickets, ensuring that we again sold out. It also made a considerable impact in its own right.

The Colman Getty campaign was in full swing as well with Amy Maclaren and Libby Appelbee doing tremendous work. At least 27 articles were to appear about or mentioning the Convention in 9 national papers, for example running Pullman in the Saturday The Times a week before the Convention. There was also some regional coverage.

Fundraising continued throughout these weeks, on the basis of the 11 January document. A number of the initial funders came through with an additional £5,000 each, a new funder gave £5,000 and the Sigrid Rausing Trust gave £10,000 in mid-February, finally ensuring that all costs would be covered not least the filming for webcast. The final costs came to £155,000 (Doc 16)

There had been a number of planning sessions with Andrew Morton at the Logan Hall coordinating everything from catering to dressing the venue. There was a high-tension moment when it seemed we might not be permitted the much-advertised live webcasting of the main sessions. We also ran into problems about how to do it. Eno put Barnett in touch with Jake Dowie, who superbly got us over that hump. Morton and the IoE team were superb,, contributing a lot to the success of the event. Meanwhile, Taylor had started to put in place volunteers for videoing all the 22 parallel sessions. They were led by Ellen Vellacott (who then also oversaw their upcasting onto the web after the Convention).

The final fortnight of February saw a great effort going into the programme that would be given to everyone who came. It was 64 pages plus a full-colour cover and inside pages. It carried the aims of the 22 parallel sessions and adverts from nearly 50 partner organisations as well as full page adverts from the CML’s sponsors. Harris designed the cover and he and David Cross completed the layout. It went into the Convention delegates bag. The programme carried short pieces by the Co-Directors headed ‘What Next?’ (Doc 14).

Behind the scenes, the days before the 28 February included a clash in emails and by phone as to whether the Convention could carry on in any organised way as a movement that could communicate with the database of nearly 2,000 people. The argument was not allowed to spoil the day.

Porter made sure that the team booked a meeting room in the hotel opposite the Logan hall, from which the team worked on the day before the Convention, as packs were prepared, press coverage encouraged, dressing the hall and the breakout sessions, and video coverage organised.

Taylor and Preston led the volunteer effort among them: Craig McLean on the electronics, Nick Cavendish driving, Patrick Hayes who was lent to us by the Institute of Ideas and (paid a little) Phoebe Dickerson.

The combination of publicity, social networking, word of mouth, briefings, videos, meetings and above all the importance of the issues themselves, saw over 8,000 people a day visiting the website the week before the Convention.

The event itself was a sensational success.

Some concluding statistics have been provided by Coatman, our Participation Manager:

- 27 articles about or referencing CML appeared in 9 national and one London newspaper

- 393 online articles or blogs about or referencing CML were published

- Over 50 blogs displayed a CML button or banner

- Our Facebook group had 2,115 members

- Our research team produced 7 briefing papers

- Our video team produced 22 videos with an average length of 2 min 38 secs. They have collectively received 33,369 views.

- Each of the 29 sessions and keynotes were filmed and are all available on the website across 28 hours, 8 minutes and 40 seconds of footage

- Over 1300 people attended in London

- There were more than 200 names on the returns list

- 142 speakers gave their time

- 40 stewards volunteered to help on the day

- 760 people attended Conventions across 7 locations around the UK

- We were partnered with 50 organisations

It will be a matter of debate as to how far the Convention shifted public opinion and influenced the political class and whether it will feed into an eventual movement, as many of those who attended desired, see the sample of the hundreds of emails that flooded in to the organisers over the days that followed (Doc 17).

In direct organisational terms two of the sponsoring organisations, Liberty and NO2ID, insisted on what they argued was the agreement that the Convention database of nearly 2,000 names could only be communicated with once. The tensions that had been present throughout the four sponsor meetings (for extracts Doc 18) came to a head at the post-Convention meeting, held at the Guardian offices 5 March.

The concluding words can be given to Aitchison, our Deputy Director, who summarised the reason for the Convention in his video:

“By coming together we are sending a powerful message to the ruling class: that our freedoms, our rights, our privacy and our personal information belong to us, and not to the State.”

![[VIDEO] Medley](https://i1.ytimg.com//vi/F7bUbkZpzCQ/default.jpg)

![[VIDEO] New Medley](https://i1.ytimg.com//vi/jwn0cVa3ZVg/default.jpg)

![[VIDEO] Guy Aitchison](https://i1.ytimg.com//vi/cHjZyDKTjLQ/default.jpg)

![[VIDEO] Helena Kennedy QC](https://i1.ytimg.com//vi/aTZCqSarlXE/default.jpg)

![[VIDEO] Brian Eno](https://i1.ytimg.com//vi/uL4nJAOKm8A/default.jpg)